August 23, 2021

Uncategorized

Could European battery manufacturers be held up by access to technology?

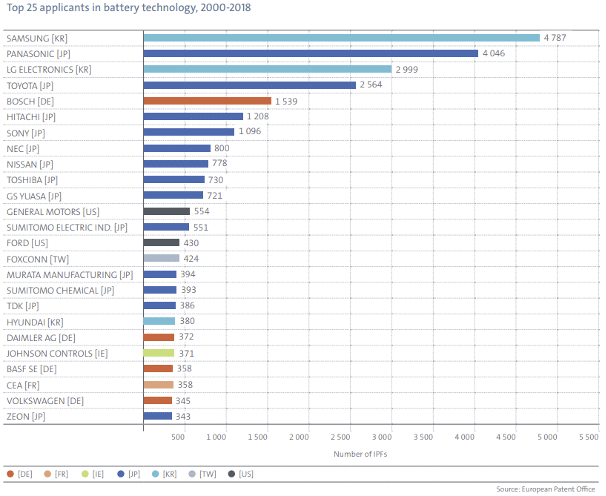

There is no denying that when it comes to Li-ion battery cells Asia is the dominant market, with lead manufacturers hailing from China, Japan, and South Korea. But change is afoot as battery production in Europe steadies for exponential growth in the next few years.

Will new European manufacturers like Verkor have the room they need to take on the Asian giants? Can they truly offer industrial-scale technology when Asia holds most of the expertise and intellectual property? In this piece we take a closer look at the concept of intellectual property in relation to Li-ion battery cell production.

What is intellectual property?

There are two main branches of intellectual property: industrial property, covering patents and expertise, and literary and artistic property. Much of battery manufacturing falls under industrial property, although aspects of literary property may apply in the area of digitalisation (software and database rights).

Given where things currently stand, is it possible to produce Li-ion batteries in Europe? How do European manufacturers plan to tackle these issues?

Let’s start by considering the strategies companies use to fully exploit their intellectual property. First case in point: an R&D team in a beverage company develops a new soft-drink recipe as well as a new method for carbonating the formula. This new and innovative system can be patented.

Next case in point: an R&D team develops a new prototype for a tent that pops up in just two seconds. The invention is based on a new and innovative arrangement of arches, and anyone who buys the product will be able to build their own by reproducing the model.

In the first case, the innovation is an in-house recipe which, if patented, will reveal a company secret. In the second case, the innovation is visible and therefore easy to replicate. Different strategies will therefore be used to leverage these two ideas. The second example is a better candidate for a patent.

Before embarking on a strategy to optimise an invention, the individual situation needs to be analysed. For instance, not every aspect of Li-ion cell manufacturing has been patented, as some manufacturers want to keep certain methods confidential. This means that a future manufacturer can develop its own in-house expertise by studying in detail the state of the art (or prior art) and the list of pending patents on European territory.

What is a patent?

A patent is a negative right, or the right to prevent a third part from using the content of the patent held by its owner. It is not an authorisation for the inventor to commercialise the invention. To clarify, let’s say Company X holds a patent for [A+B]. Company Y, proves that [A+B+C] is more effective. Since [A+B] is protected by a patent, Company Y will have to negotiate the use of [A+B] in order to implement [A+B+C].

Note, however, that a patent filed does not necessarily mean a patent granted. A number of patentability criteria — including novelty, inventorship, and industrial applicability — need to be met. The last letter of a patent’s reference number generally indicates whether or not a patent has been granted: in most countries, “A” means the patent has been filed, and “B” means the patent has been granted. While a patent is often only granted several years after it was filed, it is protected as of the filing date.

A patent comprises a description and “requirements”. These “requirements” define what needs to be protected. With respect to batteries, many kinds of patents exist, and are subdivided into families with distinct codes. Class H01M4/366 covers inventions relating to the composition of a material for Li+ ion storage. Class H01M4/131 covers methods for obtaining electrodes containing said material. While the first class lies upstream of cell manufacturers (which are supplied by the chemical companies that produce the material), the electrode production method is well within manufacturers’ scope of activity. For example, any cells manufactured using counterfeit material are by definition considered counterfeit as well! There is a multitude of sub-categories covering all the battery’s base technological components, including their manufacture and use.

Patents are vastly complex, with tens of thousands of them worldwide applying to battery manufacturing alone. So, how can European Li-ion battery manufactures identify which of these present a hurdle to their commercialisation efforts?

Geographic regions and term of patent

An important concept here is geographic scope. Every patent has a defined scope by which it is applied to a given territory — mostly national. Thousands of patents are only valid in China, for example. It is therefore essential to look at what regions apply. Then there is the fact that companies sometimes lapse on their fee payments, stripping the patent of its restriction rights. And while this is less often the case with strategic patents, the patent “lifespan” of 20 years adds an additional layer of complexity. For 20 years the applicant will pay fees to keep the patent on line, after which it falls into the public domain.

To conclude, new market players will need to closely scrutinise historical manufacturers. A critical part of this exercise will be to clearly map out the pending patents in the territory, and pinpoint their subject matter in order to determine to what extent it can be used. Strategic partnerships and patent licence agreements are also an option. Clearly, there is ample room for European manufacturers to develop their own Li-ion battery technology.